The Steinway Teflon bushing has gotten a lot of bad press through the years, and although some of that is deserved, I think the time and effort Steinway put into it is not well known.

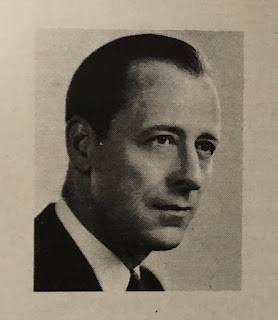

Theodore D. Steinway was the chief engineer at Steinway during the time of the development of the Teflon bushing (during the first three years of the decade of the '60's), and was in charge of all the research and development in design, methods and materials of piano construction. The impetus of this development of using Teflon for centers stemmed from the comparative expense and complications that the cloth bushed parts posed to the manufacturer. Tight controls and highly skilled personnel were among the things required to properly manufacture these cloth bushed parts, adding time and expense for the maker.

Theodore D. earned a B.A. from Harvard in 1935 and worked at Steinway & Sons since 1935 starting with a three year apprenticeship at the factory. During WWII he served in Army Intelligence in the Pacific and rose to the rank of Major before his release after which he returned to the factory. Theodore and his team began working on this idea in the late 1950's. They came upon the idea of a one piece bushing made of TFE fluorocarbon resin known to us as Teflon, and dubbed by its creators, the permafree bushing.

They tested these bushings over more than 8 million cycles which they figured equated to 40 years of hard playing and found no appreciable change in performance. They did test other materials which they found to have fair results, such as polyethylene, vinyls, nylon and rubber, but found Teflon to be somewhat superior to those.

Hygroscopic properties of Teflon are practically zero, as its moisture absorption was found to be less than 0.01%, in contrast to the 8% moisture picked up by the wool cloth bushings, when relative humidity changes from 25 to 75%. In the comparative trials in the high humidity environment, centers equipped with Teflon bushings required 7% more force to play the keys, due almost exclusively to the wood and not the Teflon, where cloth centers required 65% more force, and at times failed to function due to tightness.

In trials dealing with low humidity, the Teflon lost 8% of the effort needed to play the keys but were still firm and solid. The cloth bushings lost 16% and wobbliness was evident in many cases. Excessive looseness results in squeaks and noises, and in inaccurate alignment of hammers, inefficient control and poor operation of the keys.

Now the main complaint with Teflon bushed parts these days and in days not long past are that they distort due to the wood surrounding them, much more than the above tests indicated. With high humidity, the bushings would click and become somewhat loose, whereas their tests with high humidity netted no such results, probably due to the fact that the high humidity test was of relatively short duration, because prolonged humidity rise and fall through many years does eventually result in loose bushings in high humidity. In a dry atmosphere the opposite eventually happens, again, not immediately, but in time, where the centers become tight.

Steinway used to send their technical people out to teach piano technicians how to fix these things. I don't think they thought they would be as much of a problem as they turned out to be. I remember taking a Teflon class from Fred Drasche at the 1980 Piano Technicians Guild annual Convention in Philadelphia. I remember learning how easy it was to fix and how to replace the bushings and how to ream them with specialized reamers and center pins. One thing to remember was when re-pinning Teflon bushed parts, we were to pin the parts a bit looser than done with cloth bushed parts, but not too loose where they would click. It was a more precise effort and required acquiring experience to accurately do the work.